By Maureen Tai, 20 March 2022

Some months ago, I had the pleasure of hearing literary translator, Avery Fischer Udagawa, read an excerpt from J-Boys (ages 10 and up), a refreshingly unique, memoir-style middle grade novel set in post-war Tokyo. I was so taken by the reading that I vowed to track down the book to share with my 11-year-old son, a feat I accomplished only several months later, but it could not have been more timely. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine had just begun and anxiety-inducing pronouncements of World War III were being shared and reshared on his school chat rooms like a nasty piece of schoolyard gossip. The time had come to talk about the reality of war, not as a vaguely discomforting series of grim facts from an unconnected past, but as a terrible ever-present violence that humans are capable of inflicting upon one another. What I didn’t expect was how J-Boys would help me frame that conversation.

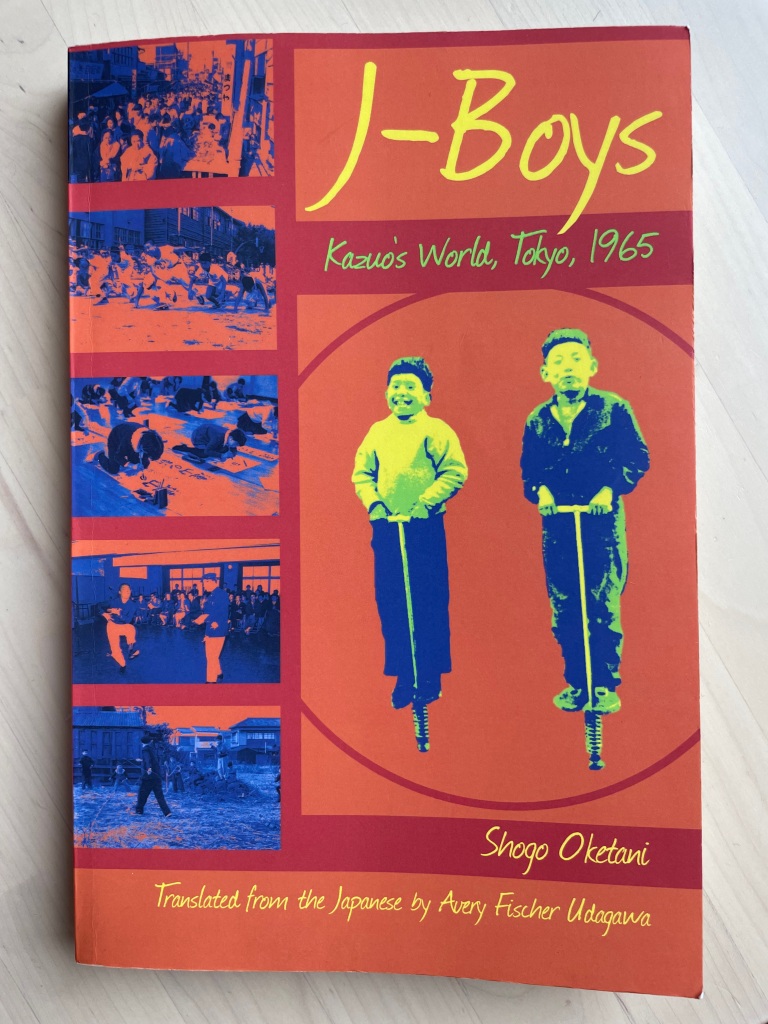

J-Boys chronicles, in a series of linked, short stories, the life of a fourth-grade Japanese schoolboy, Kazuo, spanning 8 months in 1965. World War II ended two decades ago but its long shadow lingers, in particular for those who lived through those turbulent times. The effects of the war – nothing gory or grisly – are referred to fairly frequently throughout the book. Fortunately, Kazuo’s world, compared to that of his parents’, is infinitely more idyllic. He lives with his mum, dad and dog-obsessed younger brother in small but comfortable company housing. He does his homework in front of their black-and-white TV. He has a posse of friends who become the titular J-Boys: Nobuo, the butcher’s son, Minoru, a Korean boy, and Akira, a professor’s son. After school, they play in an empty lot before heading home for family dinners where fresh tofu – which Nobuo dislikes – features prominently. Kazuo loves curry rice, but hates miruku, a foul-tasting skimmed milk beverage that is forced on school children. He loves watching TV, but hates studying. He longs to try an American-style hanbaagaa (hamburger) but has to settle for a wafu (Japanese-style) hanburuguru steak instead (inexplicably, the word hanburuguru becomes my son’s new favourite word). While the events in Kazuo’s life are semi-fictional, the non-fictional elements of the setting are – or were – real, as explained in small shaded text boxes, unobtrusively interspersed with the narrative.

In these hyper-fast, instant-gratification times that we live in, we forget that what nourishes the body most is a long, warm soak in the bath, not constant jolts to the senses. J-Boys is not an irreverent graphic novel, page-turning adventure, nail-biting mystery or inspirational story of triumph-over-adversity, which are the narrow categories that most popular middle-grade books seem to fall into these days (to my chagrin). What it is, is an authentic, gentle, amusing yet poignant meander through the memories of a young boy growing up in a post-war world. It is a boat trip on a river, not a roller coaster ride. It is a comfort, not a distraction. Particularly for me, a child of Kazuo’s generation, it is a reminder that there is a light at the end of the tunnel, however long and devastating that tunnel might be, and that is a reminder worth sharing with future generations.

For ages 10 and up.